|

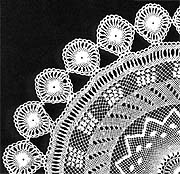

The Origin of Lace In Asia Minor where Armenians had lived for centuries and particularly in the Armenian plateaus, nearly every woman knew the technique of combining spinning threads of wool, linen, flax and cotton, and making textiles, carpets, laces and embroideries. In every part of Armenia, and wherever Armenians colonized, it was their custom to make and donate embroidered articles, textiles, carpets and laces to decorate shrines, temples and churches. Because Armenians worshiped either standing or kneeling, large carpets and rugs were donated to every church by faithful artisans on occasions such as weddings or christenings. Cathedrals and churches became, like the homes, great repositories of antique handspun, hand-woven fabrics and laces. The magnificent vestments of Armenian clergy were renowned. Though the art of making embroidery and finer needlelace was taught in Armenian church schools, convents and monasteries, secular embroidery and lacemaking were taught at home and in workshops. It is not known for certain where the first lace or anything resembling lace or embroidery was made. One can find clues through a study of the materials required for making lace and other fabrics. The essentials were: Raw products such as hemp, flax, cotton, wool and silk for threads. Vegetable, animal and mineral sources for making dyes. Metallic tools for durable looms, frames, hoops and other wooden implements for spinning thread, doubling, preparing the web warp and wood. Hard wood for durable looms, frames, hoops and other wooden implements for spinning thread, doubling, preparing the web warp and woof. Ancient Armenia possessed and produced all of these essentials. The late Serig Davtyan, well known authority and scholar of Erevan, in her book, Haygagan Djanyag (Armenian lace), published in 1967, states that in Van, the capital of the Urartian Kingdom, women made lace from the fiber of djout (pronounced jute). The Armenian word djout or djot was used to describe the fine fibers of hemp as well as the lace made of the fiber. Flax, called voush or kutan, was also used for lace. Like that of jute's, its existence in the Stone Age has been documented. The cultivation and preparation of both fibers were almost identical. When the plants of hemp and flax had ripened, they were pulled from their roots, never cut. The stalks were then washed and immersed in water warmed by the sun. The immersed stalks were pressed down with heavy weights. They were then rippled and dried in the sun. When completely dried , they were carefully beaten with mallets on stone slabs. The fibers nearest to the rinds, being short and coarse, were used to make rope. The finer inner portions of the stalks were bleached in the sun or in a mild alkaline solution then combed and spun into fine threads. Flax and hemp were used for making nets to catch fish, birds and animals, also for making strong, heavy cords to tie goods for transport. It is fascinating to realize that the ropes used in moving heavy stones for building enormous monuments were made from fibers of the same plants that produced the extremely delicate yet strong fibers for the filmiest of laces. The earliest handmade lace was most likely done in the form of a net. From coarser large looped nets, finer nets with smaller loops were gradually developed. It is safe to assume that the Armenian knotted needlelace developed out of the earliest fish nets. At first lace was made by knotting or weaving with the fingers. Primitive women later improvised tools form fish or bird bones. Armenian knotted laces required tools of iron, and there is evidence that the people of Armenia possessed iron ore centuries before any other peoples had discovered it. (See the traditional crafts of Persia by Hans E. Wulff.) Having learned the process of the cementation of iron and the production and hardening process of steel, they were the earliest people to have used iron or steel tools and, consequently, the metal needle. Once the needle was invented and metal shuttles were produced, the progress of lacemaking, embroidering and weaving advanced very rapidly. Whereas the Armenians used iron or steel needles probably as early as 1000 B.C., steel needles were not manufactured in Europe until 1370 A.D. Khoren, the 5th century Armenian historian, refers to the use of gallnuts for dye. Arab geographers wrote of the "cochineal dye derived from a kind of worm which weaves a cocoon around itself." These worms were abundant in the valley of Ararat and were widely known and sought as far away as India. Each fiber was treated separately with a specific mordant or fixer because wool, silk, cotton or linen reacted in different ways to the same dye. Logwood gave a bluish-black color which was used for dyeing cottons and wool.Vortan garmir (or cochineal) was the fast red color for wools and silk. Turmeric berries, onion skins and other vegetables gave yellow colors. Catechu gave cottons and silks a fast brown color, Indigo was used to dye wools and cottons blue. Many vegetables, flowers, fruits, buds, roots and nuts were used to make dyes. Minerals were used to dye cottons mostly. In addition to the plants needed for dyes, Armenia was rich in forest of oak and walnut trees and other varieties which provided wood suitable for making strong looms, frames, hoop, rods, spindles, wheels for spinning and doubling the threads and numerous other implements with which to manufacture fibers, fabrics and carpets. The presence of the wood, the dyes the metal tools and the fibers leads this writer to the opinion that Armenia was not only the original home of needlelace but of needle arts in general. |